Finding the Roots of Entrepreneurship at the Dinner Table

An analysis of data on Norwegian entrepreneurs finds that many went into the industries in which their fathers worked and that they were more successful than those who entered other industries.

What impact does industry knowledge passed on by a father have on a son's entrepreneurial success? In Dinner Table Human Capital and Entrepreneurship (NBER Working Paper No. 24198) Hans K. Hvide and Paul Oyer tease out specific benefits of exposure to industry knowledge over the course of childhood, as opposed to exposures that result from a father's later introduction to industry connections. They call this passed-on knowledge "dinner table human capital."

Norway, where the law requires public disclosure of incomes, was an ideal setting for the study, because income is a useful, if simple, indicator of individual economic success. For business data, the researchers drew on annual financial statements submitted to tax authorities. The data include variables like 5-digit industry code, sales, assets, number of employees, and profits for 1999-2011. They also collected data from Statistics Norway on workplace, education level, gender, income, wealth, marital status, and other variables; IQ test scores were obtained from Norwegian military records for 1984-2005. Finally, to obtain information on start-ups, they analyzed and coded information from the founding documents firms submit to the Brønnøysundregistrene, a Norwegian government agency. These documents include start-up year, total capitalization, and the personal identification number and ownership share of all initial owners with at least a 10 percent ownership stake.

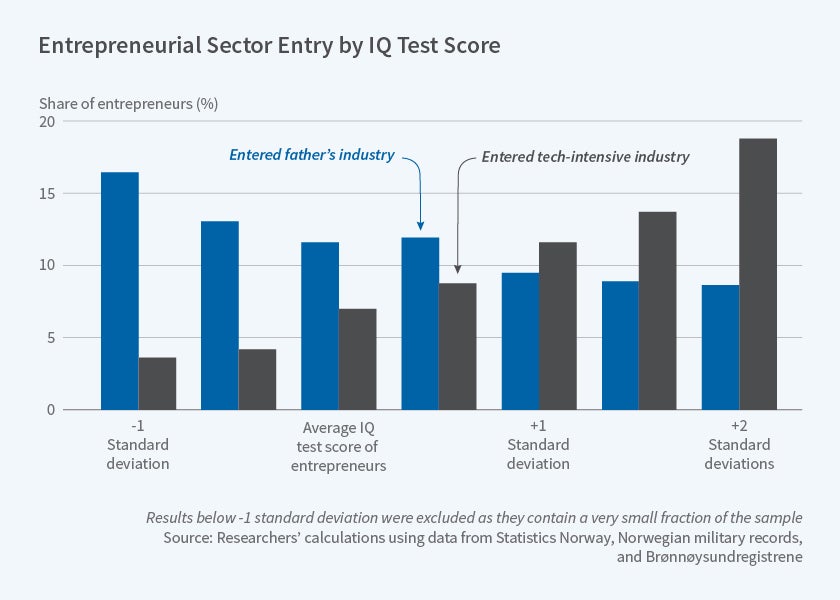

The researchers found that the majority of the entrepreneurs in their sample, which included those who were between 22 and 45 in 1996 and for whom relatively complete data were available, had gone into their fathers' industries, but that those with comparatively higher IQ test scores were more likely to have gone into other industries. This was due in part to those with higher scores being more likely to go into technology-related industries which did not exist when their fathers entered the workforce.

Entrepreneurs who went into their fathers' industries were more successful than entrepreneurs who struck out into new fields. After four years, for instance, firms founded by sons in the same industry as their fathers were not only more likely to be in business, but also had more employees than firms founded by sons who chose different industries than their fathers.

To eliminate the possibility that this was simply due to intra-industry connections and introductions that fathers could provide, the researchers looked at sons whose fathers had died before they entered the workforce and found that the rate of success was nearly the same as for those whose fathers were alive when they entered the workforce. This confirmed the researchers' hypothesis that childhood exposure to industry knowledge, whether over the dinner table or while helping out in the family business, was an even stronger contributor to entrepreneurial success than direct parental help.

— Jen Deaderick